Abstract

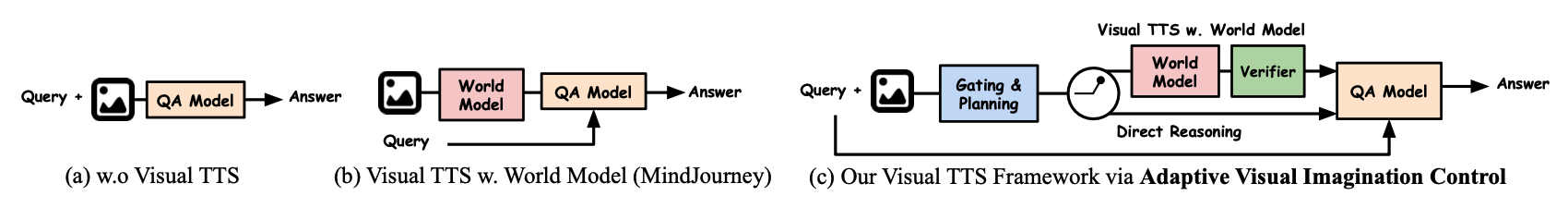

Despite rapid progress in Multimodal Large Lan- guage Models (MLLMs), visual spatial reasoning remains unreliable when correct answers depend on how a scene would appear under unseen or alternative viewpoints. Recent work addresses this by augmenting models with world models for visual imagination, yet when such imagina- tion is actually necessary, how much is benefi- cial, and when it becomes harmful, remain poorly understood. In practice, indiscriminate imagina- tion can increase computation and even degrade performance by introducing misleading evidence. In this work, we present an in-depth analysis of test-time visual imagination as a controllable re- source for spatial reasoning. We study when static visual evidence is sufficient, when imagination improves reasoning, and how excessive or unnec- essary imagination affects accuracy and efficiency. To support this analysis, we introduce AVIC, an adaptive test-time framework with world mod- els that explicitly reason about the sufficiency of current visual evidence before selectively invok- ing and scaling visual imagination. Across spa- tial reasoning benchmarks (SAT, MMSI) and an embodied navigation benchmark (R2R), our re- sults reveal clear regimes where imagination is critical, marginal, or detrimental, and show that selective control can match or outperform fixed imagination strategies with substantially fewer world-model calls and language tokens. Together, our findings highlight the importance of analyzing and controlling test-time visual imagination for efficient and reliable spatial reasoning.

Method

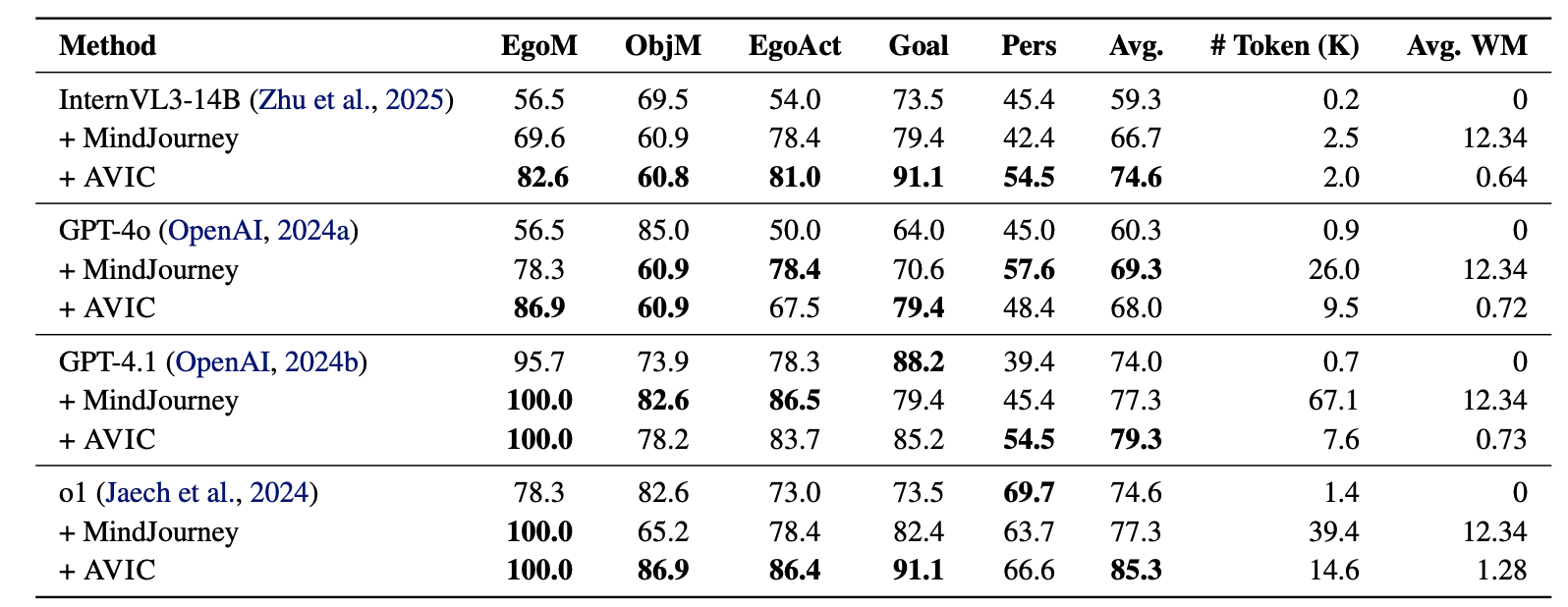

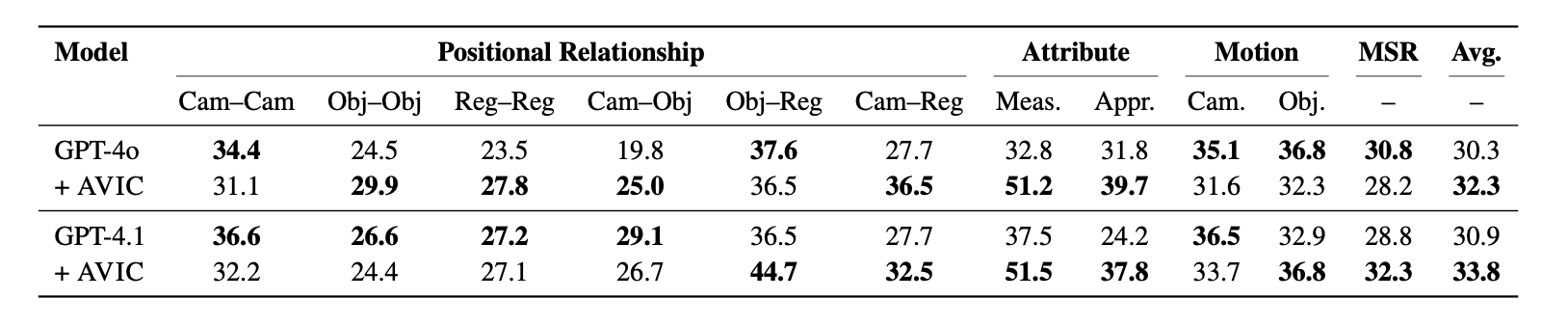

Results on SAT-Real

Results on MMSI

Results on R2R

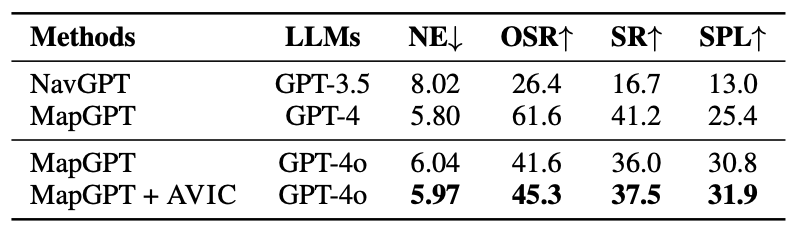

When and How Much a World Model is Needed for Visual Spatial Reasoning?

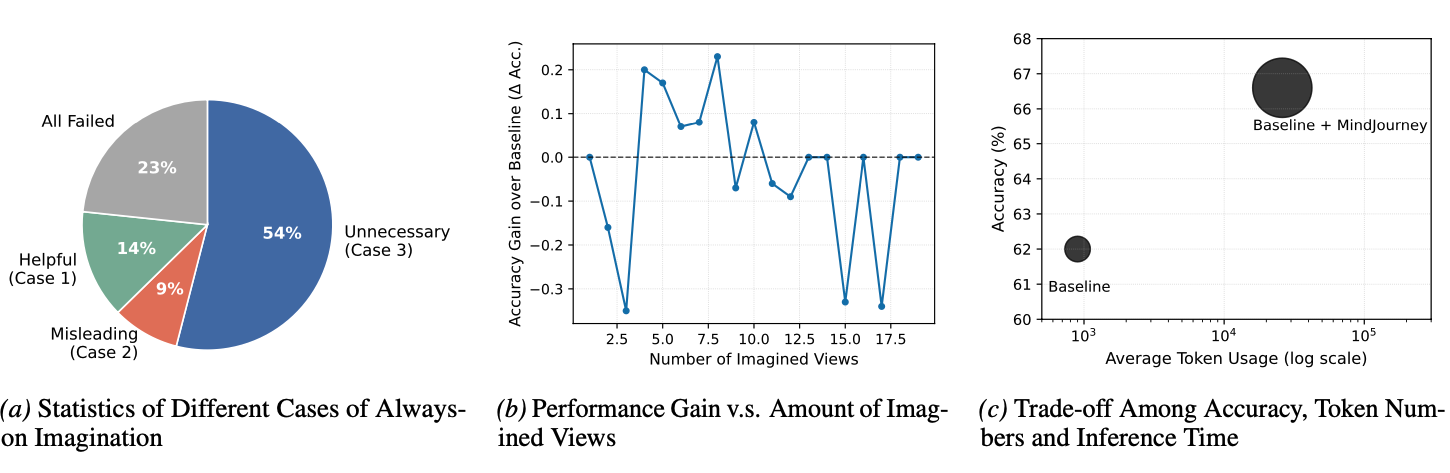

Across our analysis, we found:

(1) WM should be used selectively, primarily when spatial reasoning requires predicting future states under hypothetical actions, rather than reinterpreting existing visual evidence.

(2) Visual spatial reasoning benefits most from targeted rather than extensive WM imagination.

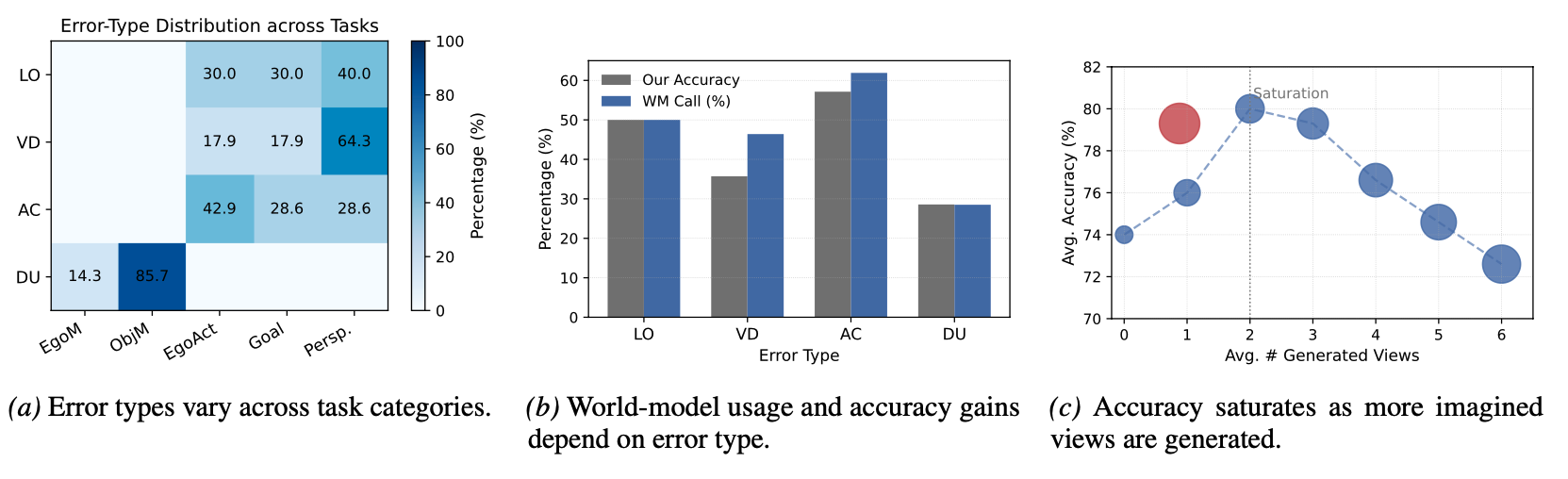

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative examples on SAT of the always-on imagination method and our adaptive method, as well as the R2R navigation task. In the navigation example, the green option is selected by the model with adaptive imagination via our method, while the red one is without world model imagination. We compare our adaptive visual TTS method with the always-on imagination method, MindJourney (MJ). In the first example, the target object (the cash counter) is already clearly visible in the observed view. Our method correctly identifies that additional visual imagination is unnecessary and directly skips world model. In contrast, MJ indiscriminately invokes the world model, generating multiple imagined views that introduce misleading evidence and ultimately lead to an incorrect prediction. In the second example, AVIC yields the correct answer by selectively imagining the state where the agent is in front of the trash bin. In contrast, MJ performs dense imagination and generates views that do not accurately reflect this critical spatial condition, leading to an incorrect prediction. Furthermore, we present a qualitative navigation example at the bottom. Our adaptive visual test-time scaling selectively augments informative indoor observations (e.g., zooming in or turning to explore nearby views), enabling the agent to better inspect the environment and align its actions with the global instruction (“go to the kitchen”). In contrast, the baseline without visual imagination lacks sufficient perceptual evidence and consequently chooses an incorrect direction.

BibTeX

@article{yu2026when,

author = {Shoubin Yu, Yue Zhang, Zun Wang, Jaehong Yoon, Huaxiu Yao, Mingyu Ding, Mohit Bansal},

title = {When and How Much to Imagine: Adaptive Test-Time Scaling with World Models for Visual Spatial Reasoning},

journal = {arxiv: 2602.08236},

year = {2026},

}